The CFA Franc, a colonial, servile and predatory currency

- Genesis of a colonial currency

- A servile currency: the proof by those who refuse

- A predatory currency: proof from the 1994 devaluation

- A rising dispute

This post was originally published on https://www.cadtm.org/ by Saïd Bouamama ( 2018-07-24 )

For the first time since independence, public demonstrations in several African countries (Dakar, Cotonou, Libreville, Bamako, etc.) and in the Paris region demanded the disappearance of the CFA Franc, a currency imposed at the time of independence on 14 countries by French colonialism. Driven by youth movements, these mobilizations mark the entry on the scene of a new generation of African activists. It is no coincidence that it is the CFA Franc which is targeted in the arsenal of dependency imposed by the colonizer in the 1960s. All the other colonial monetary zones have, in fact, ended with the dissolution of the last, the Sterling Zone, in 1979 .

This currency, presented by the French State as a symbol of cooperation, appears more and more for what it is: a provocative symbol of colonial dependence which, in addition to the CFA, has other tools: debt, the of Economic Partnerships (APE), defense agreements, the Francophonie. “While the other African currencies symbolize the break with colonization and the independence acquired in the early 1960s by name (naira in Nigeria, cedi in Ghana, dinar in North Africa), the currency circulating from Dakar to Yaoundé passing through Abidjan, Lomé, Bamako and Malabo continues to refer to the colonizer” summarizes the jurist Yann Bedzigui.

Genesis of a colonial currency

The Franc zone was officially created in 1939 during the world war in order to “constitute a “war chest” and to anticipate the instability resulting from any global conflict situation”. Previously in the French colonies an “exceptional privilege” was entrusted to private banks allowing them to issue francs with the same parity as the metropolitan franc. The first concern at the dawn of the world war was to avoid the flight of capital which led, explains a document from the Banque de France “to strict exchange control and the inconvertibility of the franc was then imposed on the outside a geographical area which includes metropolitan France, its overseas departments and its African and Asian colonies”.

During the occupation the Germans imposed a specific occupation currency which in many respects functioned according to principles similar to those which would preside over the establishment of the CFA Franc in 1945: A local currency dependent on the Deutschemark, an exchange rate between these two currencies fixed in Berlin, the drainage of resources for the benefit of the occupying power, a statutory control of the central bank by a German commissioner, etc. “The way in which money was transformed during the Second World War in France is exemplary of a subordination of the monetary to the political. […] the occupier’s purchasing power was artificially more than doubled and enabled him to acquire wealth at a lower cost. This was part of the policy of draining French resources for the benefit of the Reich,” summarizes the economist Jérôme Blancs.

At the end of the Second World War, the Francs CFA (Franc of the French Colonies of West Africa and Central Africa) and the Franc CFP (Franc of the French Colonies of the Pacific) were created. Just as in May 40 the Nazis arbitrarily fixed the value of the mark at 20 French francs, the decree of December 25, 1945 creating the CFA franc and the CFP franc fixed the value of the first at 1.7 metropolitan Francs and that of the second at 2.4 Francs. We are indeed in the presence of a currency of occupation. This relationship leads the Ivorian economist Nicolas Agbohou to speak of “monetary Nazism” in his book “The CFA Franc and the Euro Against Africa” which has played an important role in raising awareness leading to contemporary anti-CFA mobilizations.

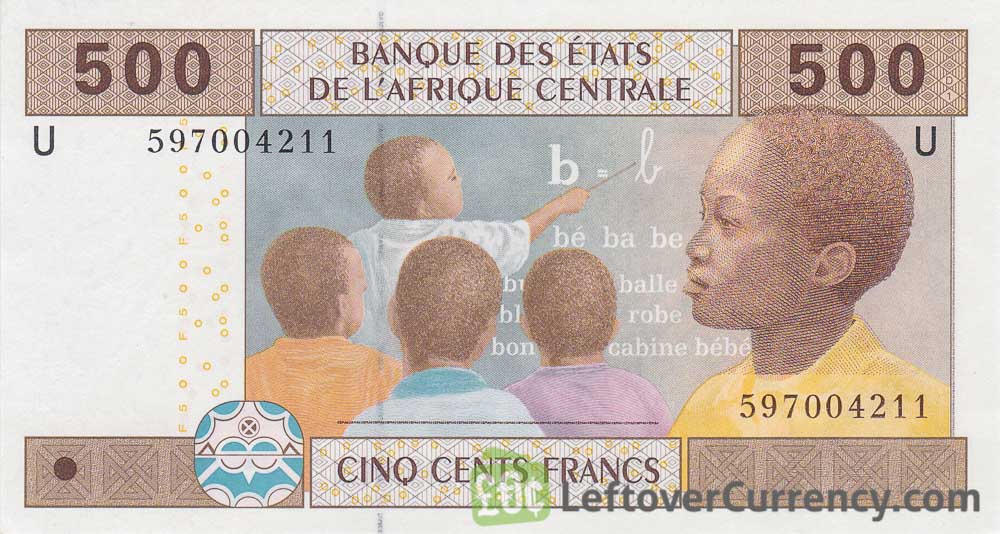

The fear of a radicalization of the national liberation struggles in the 1960s led General De Gaulle to initiate a decolonization that did not lead to real independence. To do so, it was necessary to corset the new states in cooperative relationships that systematically built economic dependence vis-à-vis Paris. The colonial link became a neocolonial link. In this context, the Franc zone and the CFA Franc are maintained with just a facelift to take account of independence: The Franc of the French Colonies in Africa becomes the Franc of the African Financial Community for West Africa and Franc of Financial Cooperation in Central Africa. The Franc zone before and after independence is governed by the same five imperative rules giving control of the economic policies of the countries of the franc zone to Paris.

The first rule is that of “the centralization of foreign exchange reserves” by the Bank of France. That is to say the obligation to deposit an essential part of the foreign currency reserves of the countries of the franc zone (65% until 2005 and 50% since) at the Banque de France. These reserves are no longer at the free disposal of States that are officially sovereign. These deposits are placed for the benefit of the French economy and generate interest. The control of half of the revenues of African countries is thus placed at the service of the French economy. The sums thus stolen from the countries of the franc zone are estimated at 8,000 billion CFA francs in 2014 by the Congolese economist Stéphan Konda Mambou, or 12 billion euros.

The second rule is that of the fixed parity between the CFA franc and the Franc then since the establishment of the Euro with it. The value of the CFA Franc compared to other currencies (dollars, Yen, etc.) varies according to percentages equal to those of the variations between the euro and other currencies. When the euro falls or rises against the dollar, for example, the CFA Franc does the same. This is in fact a real negation of African economies. The countries of the Franc zone are deprived of the possibility of acting on the exchange rate of their currency whereas this lever explains the economist Jean-Luc Dubois is an “instrument of economic policy of particular importance since these countries produce and export commodities and must become competitive in the international market”. The peg to a strong euro penalizes exports to destinations other than the European Union.

The third rule is free transferability. There is therefore no limit to money transfers to Europe and France with this rule. Looting is legalized. The profits made in the area are repatriated to Europe, making Africa a financier of Europe in general and France in particular. Repatriation becomes the rule and local reinvestment the exception. The flight of African capital to Europe is thus estimated at 850 billion dollars by the Senegalese economist Demba Moussa Dembélé between 1970 and 2008.

The fourth rule is advanced as the positive counterpart of the previous three. These three rules are set out as conditions to “benefit” from the latter: the guarantee of unlimited convertibility by the French treasury. If a State in the Franc zone is unable to ensure payment in foreign currency for its imports, the French treasury undertakes to supplement it by providing the missing foreign currency. Anyone with CFA Francs is guaranteed to be able to convert them into foreign currency. This convertibility is , at the height of cynicism, not valid for the different CFA francs between them with a logical effect of discouraging inter-African exchanges. The last rule establishes direct dependence through the co-management of the two African central banks in the zone: the BEAC (Bank of Central African States) and the BCEAO (Central Bank of West African States). Four French administrators sit on the board of directors of the BEAC and two on the BCEAO. Above all, unanimity is required for any important decision. Concretely, it is a right of veto preventing decisions contrary to French interests. The first colonial heritage of Africa is indeed a monetary and financial neocolonialism that the historian and geographer Jean-Suret Canale summarizes as follows:

After independence, the maintenance in the former French colonies of Africa of the CFA Franc became an instrument of French neocolonialism, giving France control of their economy and a privileged position for French companies. African states had practically no right to control their currency, issued by issuing institutions whose headquarters were transferred from France to Africa only in 1972-1973. France had the currencies obtained by the sale of African raw materials […] Free convertibility allowed French companies to preferentially place their goods in the Franc zone, and to freely repatriate profits and capital. […] Most of the foreign assets of African states were to be placed in the “operations account” of the French Treasury, which were constantly profitable until the end of the 1970s. According to the words of Paul Fabra, economic columnist for Le Monde , the “guarantee” provided by France to the CFA Franc existed only on the condition of not having to play!

A servile currency: the proof by those who refuse

One of the proofs that the Franc zone is an essential cog in French neocolonialism is the reaction of Paris to the decisions of certain African states to leave this zone and mint their own currency (Togo, Guinea, Mali, Mauritania, Madagascar). In Guinea, the new independent state promulgated on March 1, 1960 a “reform of the monetary system” resulting in the creation of a national currency, the Guinean franc. This reform is argued as follows by the President of the Republic of Guinea, Ahmed Sékou-Touré: “It is on the basis of this reform that economic liberation will be able to take place, hitherto hampered by a financial system whose nature, characteristics and definition had remained those of the old regime, which itself depended on the economic system of the “metropolitan” country”.

Since Sékou-Touré pronounced a resounding NO to the Gaullist Community in 1958, he had been the object of constant economic pressure from the former colonial power. De Gaulle wants to make an example in Guinea by sanctioning the one who had dared to say in response to the blackmail at the end of French “aid”: “We prefer poverty in freedom to wealth in slavery […] We do not we will not give up and we will never give up our right to independence”. The French civil servants and technicians are immediately withdrawn after this speech, a real financial haemorrhage is organized. It is also in response to these economic pressures that the decision to mint a national currency is taken. The director of the Central Bank of Guinea gives the following context of this decision: “It was a question of avoiding the strangulation of our economy by the power which controlled it until then. The boxes had been emptied of their contents. French companies repatriated their super profits without any control. It was the hemorrhage. However, you cannot really control an economy without controlling its currency.“

The reaction from Paris was not long in coming and took the form of “Operation Persil”. It consists of “introducing a large quantity of counterfeit Guinean banknotes into the country with the aim of unbalancing the economy,” confides one of the leaders of this operation, Maurice Robert. The operation itself is only one of the means among many others to overthrow Sékou-Touré continues, our Spook:

We had to destabilize Sékou Touré, make him vulnerable, unpopular and facilitate the seizure of power by the opposition. (…) An operation of this scale involves several phases: the collection and analysis of information, the development of an action plan based on this information, the study and implementation of logistical means, the adoption of measures for the realization of the plan. (…) With the help of exiled Guinean refugees in Senegal, we also organized opposition maquis in Fouta-Djalon. Supervision was provided by French experts in clandestine operations. We armed and trained these Guinean opponents, many of whom were Fulani, to develop a climate of insecurity in Guinea and, if possible, to overthrow Sékou Touré. (…).

The objective is certainly to bring Guinea to its knees but also to warn and threaten the other countries of the Franc zone. “Look at what will happen if you seek to emancipate yourself from the Franc zone. The choice is simple: the CFA or the permanent monetary crisis” translates the journalist Jean Chatain.

In Guinea The destabilization plan failed. In Mali, on the other hand, an identical plan led to a coup d’etat which overthrew President Modibo Keita. In this country too, the exit from the Franc zone is linked to the objective of “economic decolonization” set by the second congress of the Sudanese Union-African Democratic Rally (US-RDA) in September 1960, whose leader Modibo Keita is President of the Republic. As in Guinea, the reaction is an attempt to destabilize this time by encouraging public demonstrations in front of the French Embassy to demand a return to the CFA Franc. To do this, French agents rely on the concern of many traders about a non-convertible national currency. The trade unionist and militant of the US-RDA, Amadou Seydou Traoré remembers these events as follows:

The birth of the Malian Franc rang like a gong on the consciousness of neocolonialism in Mali and West Africa. This was too much in the opinion of colonialism and its paid agents. We had to act quickly and strike hard; overthrow popular power. The obsolescence of the tactics of hindrance and dilatory actions meant that the tactic of brutal violence thus manifested itself only nineteen days after the creation of the Malian currency in the form of a conspiracy on July 20, 1962. On occasion, they trampled on the national flag, tore up banknotes and shouted slogans such as: “Vive la France”, “Down with the Malian Franc”.

The counter-demonstration organized by the US-RDA to support the Malian Franc is massive. Protesters denounce what is now called the “July 20 plot”, with the Malian government accusing the French embassy of links with the protesters. The decision to evacuate the French military bases further sours relations between Mali and the former colonial power. “Until 1968 and the fall of Modibo Keita, overthrown by a military coup, the political and economic distances taken by Mali and France continued to increase,” summarizes the historian Pierre Boilley. General Moussa Traoré’s coup d’état in November 1968 marked an immediate rapprochement with Paris which quickly materialized with a monetary guarantee from the Banque de France on the basis of a series of conditions and in particular the privatization of state companies. The conditions having been met, the Malian debt was canceled by France and Mali took over the CFA Franc as its currency in June 1984.

In Togo, the independence leader Sylvanius Olympio opposed in the second half of the 1950s the balkanization of French West Africa (AOF) which he analyzed as a continuation of colonial domination. Having become President of the Republic, he announced his intention to leave the Franc zone and create a national currency. He will be assassinated in January 1963, on the eve of this announced release. Cameroonian authors Arnaud Roméo and Martin Fankoua describe the causes of the coup and assassination as follows:

The financial situation of newly independent Togo was very unstable. So to get out of this situation, Olympio decided to take his country Togo out of the CFA franc monetary zone, and create its own currency. On January 13, 1963, three days after Olympio began printing its own country’s currency, a band of illiterate soldiers backed by France assassinated newly independent Africa’s first ever elected president. […] Olympio’s dream was to build an independent and autonomous country. France had not liked the idea and the assassination.

Let’s finish with the Malagasy and Mauritanian cases which both resulted in an exit from the Franc Zone despite the pressures. For Mauritania, which left the monetary zone in 1973, its proximity to the Maghreb states made direct pressure more difficult. “For Mauritania, on the other hand, better endowed with natural resources, it was [leaving the Franc zone] an explicit political choice in favor of total monetary independence and which corresponds to a political rapprochement towards the States of the Maghreb” note the economists Patrick and Sylviane Guillaumont.

When in Madagascar, the exit of the CFA Franc takes place at the end of a decade of social protest combining revolts and peasant uprisings in the south of the country from 1967, a cultural and political movement of young descendants of slaves from working-class neighborhoods in opposition to French cultural domination (“the Zwam”), repeated worker and student strikes. This movement, which only became more radical over time and repressions, led to the fall of the First Republic in 1972. These struggles have in common a denunciation of French neocolonialism and the call for true independence. The exit of the CFA Franc like the dismantling of the military base of Ivato are demands that have taken root during this decade of struggle. The balance of power is such that French interference is unthinkable at this time.

The reminder of these facts was necessary to grasp the importance of the CFA Franc for French neocolonialism. Whenever pressure, interference and destabilization were possible, they were implemented to bring recalcitrants to heel. The only exits that have been accepted are those that have been imposed by the relationship of forces. It is in the light of these facts that we must judge the credibility of Macron’s remarks at the G5 Sahel summit in Bamako in July 2017. He then declared cynically: “If we don’t feel happy in the franc zone, we leave it and create our own currency as Mauritania and Madagascar did. “

A predatory currency: proof from the 1994 devaluation

We underlined above the consubstantially predatory nature of the rule of centralization of a significant part of foreign exchange reserves at the French Central Bank. This centralization allows the French State to invest these currencies and to earn interest on them. The height of cynicism, part of this money can then be counted as “development aid” and another part be “lent” with interest to African states. Here is this mechanism and its effects presented by the economist Nicolas Agbobou:

France naturally places, like any intelligent economic agent, the immense African capital in the financial establishments with the best rates of remuneration. It logically appropriates the interest rate differential. For example, it guarantees the payment to Africans of an annual rate of 2% while it receives a remuneration of 4.5%. The net interest rate differential is 2.5%. Assuming that the African capital placed amounts to 100,000 billion FCFA, France receives a net of 250 billion FCFA in annual interest. […] Of these [the resources thus obtained], France draws a small part, ten billion CFA francs for example, to lend them to the countries of the Franc zone at low interest rates of between 3% and 10% per year, drum beating in order to show the whole world its acts of generosity towards this Africa which it thus claims to help! This is called France’s financial aid to its former colonies.

The predatory character of the CFA Franc is further accentuated with the changes in the world situation from the end of the 1970s. Structural Adjustment Fund (SAP) from the International Monetary Fund:

In the space of ten years, the indebtedness of African states has increased tenfold. Under the effect of a very significant deterioration in the terms of trade, their foreign exchange reserves collapsed. Their overall trade deficit, which in 1973 did not exceed 1.8 billion dollars, has crossed the 11 billion mark since 1980. Debt rescheduling operations have multiplied (11 between 1979 and 1981) while IMF interventions have increased from 2 in 1978 to 21 in 1982.

This policy of encouraging indebtedness and then placing it under IMF control corresponds to a growing African offensive by the USA (which has a preponderant place within the IMF and the World Bank) within the framework of economic competition with the Europe that will only grow. In this regard, the political science researcher Zaki Laïdi already underlined in 1984 that “in the regional areas where the pre-eminence of the French presence was established, the World Bank managed to dethrone France in the financing of investment aid and loans outside project “. IMF like the United States will use a decade later, the blackmail at the end of the loans to impose a devaluation of the Franc CFA of 50%.

The end of the “cold war” only accentuates this American offensive in Africa. The disappearance of the USSR and the balances resulting from the Second World War reinforced competition for rare goods such as energy and strategic raw materials. Now no “common enemy” comes to curb the fierce competition between sharks. Ron Brown, Bill Clinton’s Secretary of State for Commerce explicitly summed up the new US strategy in May 1995. traditions of Africa, starting with France. We will no longer leave Africa to the Europeans”.

It is within the framework of this aggravation of competition between Europe (and more particularly France) and the United States that the enlargement of the Franc zone to countries not belonging to the former French colonial empire: Equatorial Guinea in 1985 and Guinea Bissau in 1997. The pressures of the USA, the World Bank and the IMF to obtain a devaluation of the F CFA are also part of this context. “The IMF and the American government considered that the overvaluation of the CFA Franc constituted a brake on the competitiveness and growth of the member countries of the Franc zone, and that consequently their economic recovery necessarily passed through devaluation” explains the economists Alain Delage and Alain Massiera. The same actors highlight that the devaluation facilitates the export of these countries (at lower prices of course) but are silent on the increase in the cost of imports of capital goods and manufactured products that it inevitably entails. Behind these sales arguments, what is hidden is of course the access to these African markets for American multinationals. As usual, the compromise that will be found will be made on the backs of African countries.

In exchange for maintaining its African pre-square and its function as “policeman of Africa”, Paris agreed to devalue the CFA Franc by 50% in 1994: “a reorganization of the role of official France in Africa within the framework wider range of systems developed by global financial institutions,” says historian Françis Arzalier. The two thieves agreed to starve the peoples of the countries of the Franc zone. A simple look at the consequences is enough to measure the extent of these in terms of the enrichment of the French Treasury and the impoverishment of the peoples of the Franc zone: “A French public Treasury [which] is filled with the net foreign assets of Africans whose social situation continues to deteriorate jointly, the fruits of their heavy sacrifices being transferred and stored in Paris, due to the strict respect of the monetary agreements which handicap them structurally” sums up the economist Nicolas Agbohou. The consequences for the peoples are immediate and catastrophic: “It’s a monetary tornado that hits the living conditions of the peoples concerned. The following year, the prices of drugs will have doubled! In many of the countries concerned, life expectancy will decrease over the following years. In the food sector, the shock is noticeably as brutal,” comments journalist Jean Chatain. The price of rice (which is a key element of the popular diet) has, for example, jumped by 69% for local rice and 42% for imported rice in Senegal and by 47% and 54% in Mali.

With the creation of the Euro in January 1999, the CFA Franc is pegged to the Euro, that is to say that its value now depends on that of the Euro. This peg to a strong currency has important consequences that Zéphirin Diabré, former Minister of Economy and Finance of Burkina Faso, summarizes as follows:

The CFA franc is linked to the euro by a fixed parity. The euro is a strong currency that is getting stronger every day against other currencies, especially against the dollar. Each time the euro appreciates, the CFA franc does the same, automatically. This has several negative consequences: local production costs become less competitive than those of countries outside the euro zone and exports, which are denominated in dollars, collapse, as seen with cotton.

The structural overvaluation of the F CFA by this fixed parity with the euro is not insignificant. Thus between 2000 and 2010 the dollar lost 43% of its value against the euro. The fixed parity within the framework of a strong euro policy is officially justified as a means of preserving the stability of the currency. It is actually a tool for making African economies dependent on the European Union. European companies, particularly French ones, benefit from this mechanism and dominate all economic sectors. An economic policy based on the interests of an external power: We are still in a colonial logic of extraversion with, moreover, the appearance of independent countries.

We must bear in mind this structural dependence in order to understand the continued weakening of the social fabric of the countries of the zone, the unequal development between the regions of the same country, the continued impoverishment masked by growth rates that say nothing about the redistribution of this “growth”, the desperation of a large part of the youth pushing them to migrate despite the dramatic conditions making the Mediterranean a killing machine, etc. Instability, conflicts, ideologies of despair, wars, etc. are only logical results of development made impossible, among other things by this colonial currency, servile and predatory.

A rising dispute

The fact that African heads of state (such as Allassane Ouattara from Côte d’Ivoire, Macky Sall from Senegal or Patric Talon from Benin) are stepping up to defend the colonial currency is significant of the rise of a challenge to the CFA Franc. For decades, in fact, these positions were useless as this currency seemed indisputable given the balance of ideological forces in Africa. Other heads of state are forced to echo (even remotely and euphemistically) this growing awareness. So it is on August 11, 2015 with the Chadian President, Idriss Deby who declares:

Today there is the FCFA which is guaranteed by the French treasury. But this currency, it is African. It is our currency. It is now necessary that this currency really be ours so that we can, when the time comes, make this currency a convertible currency and a currency which allows all these countries which still use the FCFA to develop. […] Africa, the sub-region, French-speaking African countries too, what I call monetary cooperation with France, there are clauses that are outdated. These clauses will have to be reviewed in the interest of Africa and also in the interest of France. These clauses pull the economy of Africa down, these clauses will not allow to develop with this currency.

Significantly, this declaration is made during the celebration of the 55th anniversary of the independence of Chad. Burkinabé President, Roch Marc Christian Kaboré goes in the same direction by declaring at the 52nd summit of ECOWAS (Economic Community of West African States) in December 2017 that “The option has always been maintained that 2020 must be the date of the creation of the ECOWAS currency”. While these positions taken by Heads of State remain in the minority and isolated, they are part of a broader context of denunciatory speaking out in which former ministers, former ECOWAS officials and academics express themselves in more and more frequently to demand either the exit from the CFA franc and the creation of an African currency, or a reform of the Franc zone. To take just one example, take that of Bissau-Guinean Carlos Lopes, Executive Secretary of the UN Economic Commission for Africa, who declared in 2016 that “The CFA franc is an outdated mechanism that should be reviewed. No country in the world can have an immutable monetary policy for thirty years. This exists in the Franc zone. There is something wrong”.

This relative and still modest liberation of the word of political and economic leaders is itself only the reflection of the militant public demonstrations which have recently developed in several countries of the Franc zone. The debate is posed by the street in a much more radical way by a new militant generation: that of devaluation. This is evidenced by the name chosen in Senegal by the collective taking charge of the fight against the CFA Franc: “France get out”. One of its leaders, the young Guy Marius Sagna, thus declares in a much less timorous and euphemistic manner than the declarations of officials quoted above:

We have called for a rally today to essentially reaffirm our opposition to the CFA Franc because we believe it is a neo-colonial currency that puts a brake on development. We must go from today beyond the denunciation of the CFA Franc and demand our exit. We believe that today, to break the neocolonial link of the F CFA, we should demand the exit of France from our central banks. France must exit, this is what we called the Frexit, that is to say the France exit, that France releases from our Boards of Directors where it has a right of veto.

This awareness has already had a first cultural translation through the constitution of a collective of ten artists from seven West African countries against the CFA Franc. Their first single entitled “seven minutes against the CFA” evokes the following question: “the FCFA must die”, “monkey money” and “move on to something else. This new militant generation is rediscovering (concrete experience of the destructive consequences of the F CFA in addition) the paths of the denouncers of this colonial currency, assassinated or overthrown, such as Olympio, Sékou Touré, Modibo keita, Sankara, etc. Legacies and experiences combine to shape a new anti-imperialist era in Africa.